Scientists have been trying to figure out, are planets similar in composition to our own ubiquitous in the Milky Way and the wider universe?

In 2016, scientists discovered a galaxy, the Trappist-1 galaxy, which, much like our solar system, consists of one star and seven planets. The planets in this galaxy are composed of materials similar to Earth, but they are all less dense. What kind of world will they be?

Seven planets with similar densities

Trappist-1, a star about 40 light-years from Earth, is surrounded by seven terrestrial planets orbiting it. This is the largest group of terrestrial planets we have ever discovered outside our solar system.

None of the planets orbiting Trappist-1 are gaseous planets, and their material composition is dense, similar to the rocky planets in our solar system like Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury.

What strikes scientists most is that these planets are all very similar in composition and density, like multiples born at the same time, which is markedly different from our solar system, where planets in our solar system all have different compositions and densities.

As early as 2018, a team of scientists from Switzerland studied and calculated the masses of the seven planets. Now, with the new data they have observed, they have successfully calculated the densities of the seven planets. It turns out that the densities of these planets are more similar than they had previously expected.

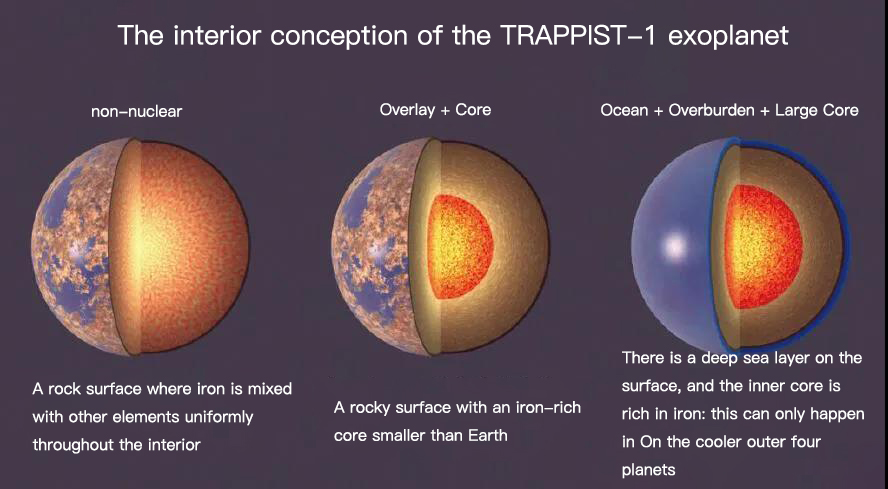

The planets in Trappist-1 have such similar densities, meaning they are likely made of the same material in similar proportions. Astrophysicist Eric Angel, who participated in the study, believes that, like most terrestrial planets, the planets in the Trappist-1 system are likely to be composed of iron, oxygen, magnesium and silicon, etc., but They are significantly different from our Earth. These planets appear to be 8% less dense than Earth, suggesting they are made up of a different ratio of matter than Earth.

Why are they less dense?

There are two possibilities for this density difference.

One possibility is that the surfaces of the planets in the Trappist-1 system may be covered with water, reducing their overall density. The researchers combined models of planetary interiors with models of planetary atmospheres to measure the water content of seven planets in the Trappist-1 galaxy.

If water were to explain this density difference, they said, for the galaxy’s outermost four planets, water would account for 5 percent of their total mass, far more than water’s share of Earth’s total mass. The proportion of mass is 0.1%).

However, the results of the calculations are disappointing. The inner three planets in the Trappist-1 system are likely to be anhydrous, and the outer four planets contain no more than 1% water.

Another possibility is that these planets contain less iron than Earth, which is 32 percent iron, compared to 21 percent. It’s also possible that the iron in these planets combined with oxygen to form iron oxide (what we commonly call “rust”), and this extra oxygen reduced their density.

The rust-red color of Mars is due to the presence of iron oxide. But iron oxide exists almost exclusively on the surface of Mars, whose core, like other terrestrial planets in the solar system, is still composed of unoxidized iron.

If iron oxide is the reason for the low density of these seven exoplanets, it means that each of these seven planets is completely “rusted” and lacks solid unoxidized “iron cores”.

The gravitational galaxy

For astronomers, the Trappist-1 galaxy is fascinating because around this star we can learn about the diversity of rocky planets in a single galaxy, answer questions about the habitability of exoplanets and questions about the possibility of life elsewhere in the universe.

Since the discovery of the Trappist-1 galaxy in 2016, astronomers have made numerous observations of it, whether with space telescopes or ground-based telescopes, only with the Spitzer Space Telescope operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Just over 1000 hours.

The night sky is full of planets, and it’s only in the past 30 years that scientists have been able to really begin to demystify them. In any case, scientists are always “ambitious”, and they always want to know if there is a home outside our planet that is suitable for us to live in.

Comments