In 1998, Portuguese writer Saramago won the Nobel Prize in Literature. When the media interviewed another national writer Antunes and asked him his opinion on the matter, Antunes hung up the phone on the grounds of poor signal. This anecdote probably reflects the relationship between this writer and Saramago in Portuguese literature. They are the most representative heavyweight writers, and they are also two people who do not give in to each other in literature.

Antunes, who has personally experienced colonial wars, medical experience, and witnessed the social transformation of Portugal in the 20th century, has a lot to suppress the style of his novels. He does not talk about fables, but about the dark and broken times. He hopes that readers will experience the severely ill Portuguese society in a way of “infected”. In the alternation of darkness and dreams, Antunes uses words to slowly unfold memories from multiple perspectives, allowing those things that have drifted away from the present to return to the readers through the stream of consciousness.

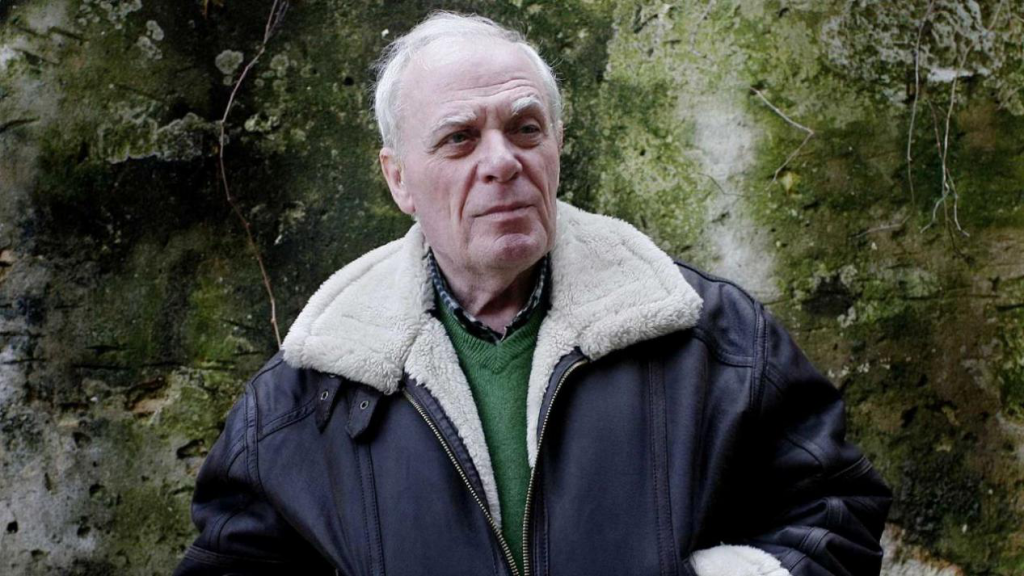

Benfica is located to the northwest of Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, where Antonio Lobo Antunes was born on September 1, 1942. The home stadium of the Benfica Football Club is called the Stadium of Light, which is one of Portugal’s landmarks. Antunes himself is also a loyal fan of the Benfica team and even participated in the team’s youth training as a teenager. A famous bronze statue was erected outside the Stadium of Light, depicting Eusebio, a legendary black forward who was active in the 1960s and 1970s. Someone once said that Antunes is Eusebio of the literary world. In response, Antunes himself responded with his iconic cold humor that Eusebio brought him happiness, but Antonio Lobo Antunes caused him trouble.

In fact, when we look deeper, apart from Eusebio’s long-term playing in Benfica, the two do have many similarities. On the one hand, they have become the symbols of Portugal in their respective fields. In the selection of “The Greatest Portuguese in History” organized by the National Television of Portugal in 2007, Eusebio and Antunes both entered the top 100.

The forward from Mozambique has been on the green field for more than 20 years. In his long career, he has maintained an efficiency of close to one goal per game. The writers from Benfica are equally prolific, with more than 30 works published in their 40-year writing career. On the other hand, after coming to Lisbon from Africa, the players ushered in a major turning point in their careers, and to some extent they became a tool for the Portuguese “new country” regime to promote racial equality. In contrast, after traveling to Africa as a military doctor, the writer’s life changed completely, and he devoted himself to using writing to deconstruct the logical system of the Portuguese colonial empire.

War: A nightmare that keeps coming back

Antunes’ father, Joao Alfredo, was a famous neurosurgeon, and his mentor was Egas Monish. In 1949, Monish won the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for his contributions to white matter resection. At this time, the seven-year-old Antonio had begun to secretly write poetry and short stories. At the age of thirteen or fourteen, Antunes read Louis-Ferdinand Celina’s “Reprieve” and was convinced by its unparalleled use of language. He wrote letters to French writers like a movie star, and actually won echo.

Celina warned the teenager who wanted to become a writer. This is not a good idea. He suggested that he study and fall in love, because if he becomes a writer, he has no time to do other things. Facts have proved that Celina’s advice is a portrayal of Antunes’s second half of life. However, before becoming a full-time writer, he went through a long period of exploration, or to use a Portuguese proverb, Antunes needs to be written in straight lines with twists and turns.

Antunes’ love of literary creation was inherited from his father. When the children were young, Joao Alfredo often read famous books for them, although the tastes of father and son were not the same. But he also does not support the eldest son’s lifelong career of literature, because the compensation for writing is too low. So when he was sixteen, Antunes still obeyed his father’s arrangements and chose to enter the university to study medicine.

In 1971, he was about to go to a London hospital to follow the footsteps of the British writer Maugham, but suddenly he learned that he was drafted into the army and needed to join the demoralized Portuguese army and set off for Angola to start a protracted war with local fighters determined to be independent.

The violence and absurdity in the war (he once asked others to read medical manuals while operating on soldiers accordingly), fear of death (one of his cousins died in the war in Africa, and a palmistry midwife predicted him Will die in Angola), doubts about the meaning of one’s own profession and national policy, the melancholy of being separated from the newlyweds, and the daughter’s inability to see the guilt of her father since her birth… It became a nightmare that Antunes kept returning.

Whether it is the early “Memory of the Elephant” and “On the Land at the End of the World” or the “Tears Committee” and “Until the Stone Becomes Lighter than Water” in recent years, it is Antunes’ reconstruction of African memories, and it is also his to review and explore the past of the nation in its own way. Words are the main medium for the sensitive and introverted dialogue and reconciliation with the world. The letter Antunes wrote to his first wife on the battlefield was adapted into the movie “Letters from the Battlefield”, which was released in 2016, but he said that he did not watch the movie because he was afraid to relive that cruel time in this direct way.

Writing: the only way to get rid of loneliness

In 1973, Antunes returned from Angola, divorced his wife three years later, and then married twice. He does not believe that divorce is the end of love, nor does he believe that death is the end of existence. After the death of his first wife Maria Jose in 1999, Antunes dedicated her the book “Don’t Walk So Fast into the Night” published the following year, and expressed that he believed she would be able to read the book .

In his opinion, the deceased are also wandering here, and the living will hear their voices, smell their scents, and speak words that only they can speak. Antonio’s two younger brothers, Pedro and Joao, died in 2013 and 2016, which seemed to make him more silent, as if he wanted to capture the traces of his younger brothers in the silence. Of course, for writers, the most natural way to miss the dead is through words that can weave time magic.

Whether it is to fight against the nightmare in Africa or to dispel the departure of those who once walked with him, Antunes’ answer is to double down in writing. Although he had been practicing medicine in psychiatry until 1985, literature is undoubtedly the focus of his life. Fortunately, with the great success of his works, Antunes can finally dance in words. For this introvert who has never used alcohol and drugs, writing is his only way to get rid of his loneliness. Any time he didn’t devote to writing made him feel guilty. When he was young, he often forget dates with companions for writing at home.

In recent years, although Antunes was worried about his age and faintness, making his works unbearable to read or over-repetitive, he planned to seal his pens several times, but his reluctance to writing made him still struggle with writing around the clock when he was nearly eighty years old. . Although the IQ is as high as 187, he believes that there is no good article in one swipe, and writing is a hard work that needs constant polishing. He rarely participates in public activities anymore, instead devoting all his limited energy to the desk.

On October 13, 2020, Antunes’ latest novel “The Flower Language Dictionary” has just come out. This book combines the characteristics of spelling from the end of the nineteenth century and the contemporary era, once again presenting the writer’s continuous attempts to make breakthroughs. Antunes has stated many times that he hopes that the remaining works can be drawn into a circle instead of leaving sharp corners. He never explained the specific meaning of the circle, only said that he liked the concept of “circle”. Perhaps in his heart, Eusebio’s football is the best representation of “roundness” and “beauty”.

World: There are black and white like football

Critics generally believe that Antunes’s first few works are more autobiographical, because most of the protagonists have similar experience in practicing medicine and fighting in Africa. However, deep down, Antunes believes that all books are autobiography. Whatever is discussed at the end is the self, because there is nothing else except self, and there is no source of information to find. “What we finally say is only the deepest things we know deep down.”

Whether it’s the Benfica trilogy in the 1990s, which shows the feelings of the homeland, or the novels with long titles in the 21st century (from personal reading or sentences heard in life), they actually have Antunes. A strong personal life mark and his silent but deep love for the general public as a pessimist. Although his writing generally refers to the development and plight of contemporary Portuguese society, in the final analysis, the depiction of human suffering and joy is the most coherent thread.

Therefore, although his books are full of violence in terms of class, gender, language, etc., these negative elements do not point to absolute depression, but only through the presentation of both true and illusion, which impacts the reader’s inherent concept. The cherishment of humanity has also given Antunes strength in real life, helping him defeat cancer three times in more than ten years. He who loves life will laughed and said that after receiving multiple chemotherapy, he was now a monster, but the world literary world will undoubtedly cherish the moments of having this monster master.

In Portugal, where Catholicism is widespread, Antunes’ father never goes to church or attends Mass. But in his twilight years, when the eldest son plucked up the courage to ask him if he believed in gods, the doctor who had been studying the brain all his life fell into a long silence. In the end, he gave the answer: “Nothingness exists in nature.” When Antonio entered old age and was asked about his beliefs, the author’s answer was: “I believe in God, but I have been angry with him.”

Antunes didn’t like himself either, thinking that he was too closed, had too many doubts, and had been in a state of civil war. But he loves the beauty of the world, such as Eusebio’s football (he doesn’t like Ronaldo’s play), such as ordinary people with wisdom, such as his five younger brothers. The experience of a psychiatrist gave him a perspective to analyze the darkness of human nature, but did not deprive him of his pursuit of the glory of human nature. This round world has black and white like football. For this dirty but beautiful world, he has been working hard for more than 40 years, which is his only and best feedback.

Comments