“You’re too old, your mind can’t move.”

In the past, most people are convinced that the reaction of the elderly is more sluggish than that of the young.

Numerous scientific studies also show that there is a negative correlation between thinking speed (the speed at which the brain thinks about problems) and age.

That said, older adults tend to think slower than younger adults across a wide variety of cognitive tasks and contexts.

However, is this true?

Recently, a research team from the Institute of Psychology at Heidelberg University in Germany found that although our reaction time begins to slow down at the age of 20, the reason for this slowdown is due to increases in decision caution and Slower non-decisional processes, not differences in thinking speed.

The difference in thinking speed, on the other hand, only appeared after about age 60.

Therefore, this study challenges the common view about the relationship between age and thinking speed.

The related research paper, titled “Mental speed is high until age 60 as revealed by analysis of over a million participants”, was published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

Older people’s brains are slow? wrong

Why do we always think that the elderly have slow brains?

This is actually due to most of the research on the relationship between age and thinking speed in recent years.

In previous studies, scientists’ conclusions on the relationship between age and thinking speed were mainly based on the average reaction times (RTs) of subjects in primary cognitive tasks (such as comparing two letters) as information processing. A measure of base speed.

However, this approach suffers from two distinct drawbacks:

The use of mean RTs alone does not exploit the full information contained in empirical RT distributions and ignores accuracy data also available from experimental paradigms.

That is, this method draws conclusions from a single result.

For example, in our daily life, when we compare the deliciousness of crayfish in two restaurants, “this one’s lobster is big, so it’s delicious; that one’s lobster is small, so it’s not delicious”, we only focus on the size of the lobster and ignore other Factors that affect the taste of lobster (such as cooking methods, freshness of crayfish, etc.) have certain limitations in the conclusions drawn.

2. Far from being a pure measure of thought speed, average RTs represent the sum of different cognitive processes.

For example, the speed-accuracy trade-off (i.e., differences in the degree of prudence of responses can affect the speed and accuracy of responses) and the time spent in coding and motor processes, although they are not related to thinking speed, can have a large impact on average RTs influence.

Therefore, the extent to which average RTs reflect thinking speed is open to question.

In addition, most studies over the past two decades have also had small sample sizes, which is especially problematic for studies of individual differences that seek to improve reliability with larger samples.

To improve the accuracy of the study, the researchers used deep learning to apply a Bayesian Diffusion Model (DM) to a large sample (including 1.2 million participants in the 10-80 age group), extracting interpretable data from raw response time data. cognitive parameters.

The researchers found that thought speed, decision prudence, and non-decision-making components (coding and motor reaction time) affected mean RTs across age groups.

“Three-pronged approach” to control your brain

So, what is the specific impact?

The first is the speed of thinking, which is what we usually call the speed of the brain’s response.

Research shows that people’s thinking speed remains stable through the age of 60, and begins around the age of 60, with an accelerated decline in thinking speed, which continues until the age of 80.

So, until you’re 60, your thinking speed is about the same as when you were 20. (So that’s why the retirement age is 60?)

The second is decision-making prudence. Decision-making prudence represents the degree of prudence when we make decisions, and we will consider the consequences of the decisions we make.

Research shows that decision prudence decreases between the ages of 10-20, after which it increases quasi-linearly until age 65.

This result suggests that college-aged people were the least cautious in their responses, preferring to trade off accuracy and speed.

In addition, a trend toward increased decision-making prudence becomes evident in early adulthood, which explains why average RTs start to correlate with increasing age in later adulthood.

Finally, there is the non-decision time, the non-decision time, that is, the time required for encoding and motor responses.

Studies have shown that non-decision time decreases from age 10-15 and then increases quasi-linearly until age 80.

Thus, age differences in decision-making prudence and non-decision-making time were strongly associated with the patterns found with RTs, suggesting that these factors may have a significant impact on average RTs levels across the lifespan.

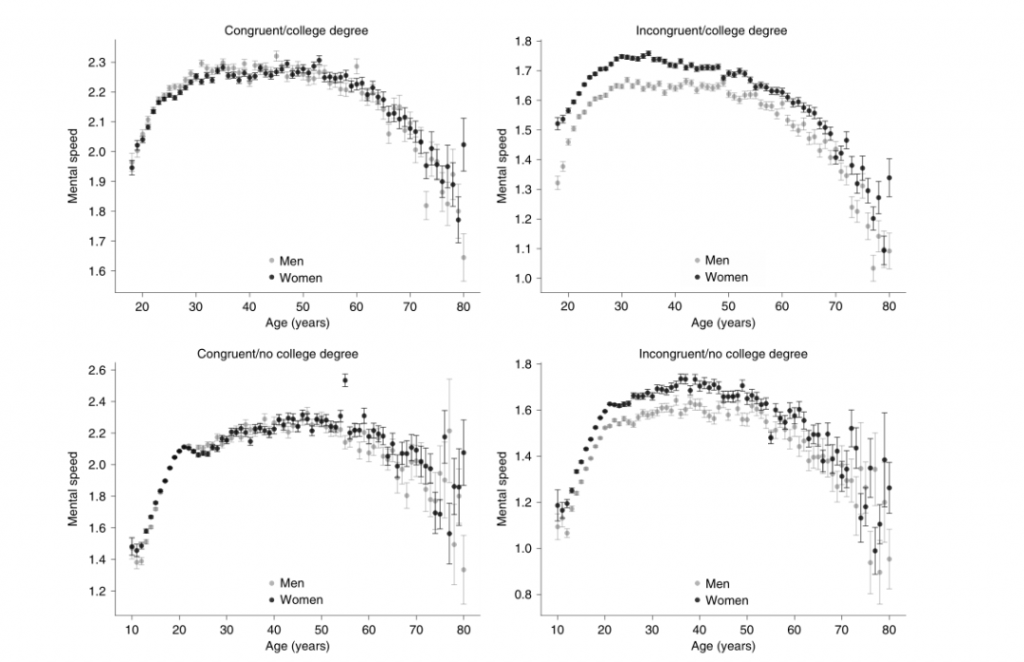

Figure | Thinking speed as a function of age, experimental conditions, and demographic variables.

Age differences in drift rates were analyzed separately according to gender, education level, and experimental conditions. (Source: The paper)

In addition to this, the researchers observed that the apparent non-linear relationship between drift rate, an indicator of thinking speed, and age was significantly different from the association implied by mean RTs, and was stronger than that found in previous DM studies. Age differences are more informative.

limitation

The different age-related patterns of DM parameters become more plausible in the context of the literature linking changes in cognitive abilities to changes in their neurophysiological underpinnings, according to the researchers.

Compared with previous studies on cognitive aging, this study has several advantages, the most prominent of which are:

a large number of samples, allowing detailed age-related analysis;

Use a Bayesian diffusion model to decompose the different components of the decision-making process in a robust and theoretically sound manner.

However, “we must be aware of some limitations of this study,” the researchers said.

These include whether the study’s data came from only one specific type of decision-making task, and whether age differences and trends over the course of the study were representative of people’s internal developmental processes (after all, people are constantly changing and don’t follow a given pattern growth) and so on. These are unanswered questions.

But the researchers are anticipating this, and they believe that while these analyses are beyond the scope of the paper, there may be some value in future work.

In short, this research subverts our traditional perception of cognition. At least until the age of 60, our brains are kept in a “young” state and can still be “moved”.

So, do you think you can “fight” for a few more years?

Comments